Cambridge, MA

A ring often serves as the visible symbol of the unseen - be it mystical, Lord of the Rings-style power or the devotion between two people. In space, a ring of light is more than a symbol. It is a guidepost to unseen matter and a beacon from galaxies in the distant universe.

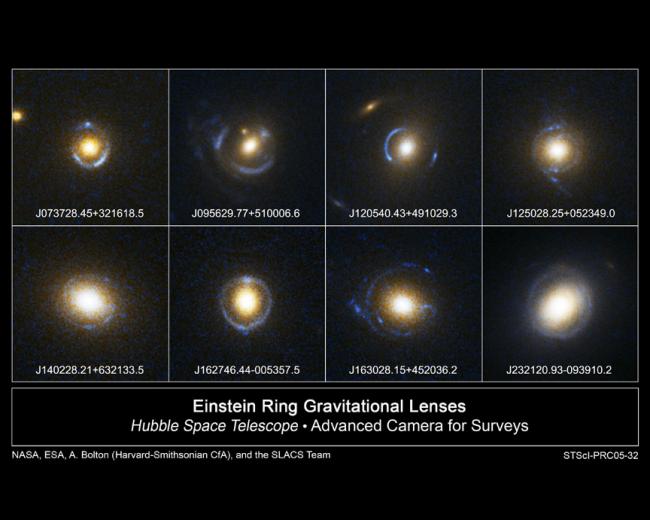

Albert Einstein predicted that such rings would be found nearly 70 years ago. In a 1936 paper, he described how the gravitational field from a massive object can warp space and thereby deflect light. In special cases, the light from a distant object can be so distorted that it creates a complete ring known as an "Einstein ring." The distortion maps the distribution of matter creating the warp and brightens the light source to make otherwise too-faint galaxies visible.

"An Einstein ring is one of the most dramatic demonstrations of the general theory of relativity in the cosmos," said Adam Bolton of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA). "It provides an unique opportunity to study the most massive galaxies in the universe."

The optical illusion created by warped space is called gravitational lensing. It is nature's equivalent of having a giant magnifying lens in space that bends and amplifies the light of more distant objects. In gravitational lensing, light from a distant galaxy can be deflected by an intervening galaxy to create an arc or multiple separate images. When both galaxies are exactly lined up, the light forms a bull's-eye pattern, called an Einstein ring, around the foreground galaxy.

Astronomers now have combined two powerful astronomical assets, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) and NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, to identify 19 new gravitational lens galaxies, adding significantly to the approximately 100 gravitational lenses previously known. By studying the arcs and rings produced by these lens candidates, the astronomers can precisely measure the mass of the foreground galaxies. Among these 19, they also have found eight new Einstein rings. Only three such rings had previously been seen in visible light.

These newly discovered lenses come from an ongoing project called the Sloan Lens ACS Survey (SLACS). A team of astronomers, led by Adam Bolton of CfA and Leon Koopmans of the Kapteyn Astronomical Institute in the Netherlands, selected its candidate lenses from among several hundred thousand optical spectra of elliptical galaxies in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. They then used the sharp eyes of Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) to make the confirmation.

"The massive scale of the SDSS, together with the imaging quality of HST, has opened up this unprecedented opportunity for the discovery of new gravitational lenses," Bolton explained. "We've succeeded in identifying the one out of every 1,000 galaxies that show these signs of gravitational lensing of another galaxy."

Besides producing odd shapes, gravitational lensing gives astronomers the most direct probe of the distribution of dark matter in elliptical galaxies. Dark matter is an invisible and exotic form of matter that has not yet been directly observed. Astronomers infer its existence by measuring its gravitational influence. Dark matter is pervasive within galaxies and makes up most of the total mass of the universe. By studying the dark matter in galaxies, astronomers hope to gain insight into galaxy formation, which must have started around lumpy concentrations of dark matter in the early universe.

"Being able to study these and other gravitational lenses as far back in time as several billions years allows us to directly see whether the distribution of dark and visible mass changes with cosmic time," said Koopmans. "With this information, we can test the commonly held idea that galaxies form from collision and mergers of smaller galaxies,"

The SLACS Survey that Bolton began at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is continuing, and so far the team has used Hubble to study almost 50 of their candidate lens galaxies. The eventual total is expected to be over 100, with many more new lenses among them. The initial findings of the survey will appear in the February 2006 issue of The Astrophysical Journal and in two other papers that have been submitted to that journal. Further information can be found at the SLACS website:

This release is being issued jointly with the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Md.

Headquartered in Cambridge, Mass., the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) is a joint collaboration between the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory and the Harvard College Observatory. CfA scientists, organized into six research divisions, study the origin, evolution and ultimate fate of the universe.

David A. Aguilar

Director of Public Affairs

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

617-495-7462

daguilar@cfa.harvard.edu

Christine PulliamPublic Affairs Specialist

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

617-495-7463

cpulliam@cfa.harvard.edu

Donna Weaver

STScI

410-338-4493

dweaver@stsci.edu