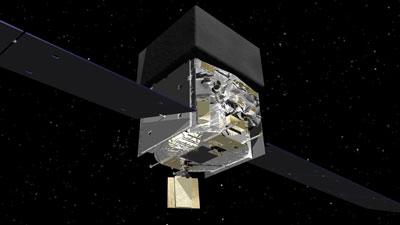

An artist's image of the Fermi Gamma Ray Telescope. SAO astronomers have used Fermi to study the gamma rays emitted when supernova shocks encounter nearby, dense molecular clouds.

Gamma rays are the most energetic form of light. They are typically produced in four ways: in extremely hot regions (temperatures of more than about 100 million degrees), when very fast moving charged particles interact with other charged particles or with magnetic fields, when atomic particles or nuclei decay, or when matter and anti-matter annihilate. Although they are energetic, gamma rays from astrophysical objects are not easy to detect, and only hundreds of celestial sources are known so far.

The Fermi Gamma Ray Telescope, launched by NASA in 2008, has dramatically improved our ability to study gamma ray sources in space. SAO astronomers Daniel Castro and Pat Slane have used Fermi to study the gamma emission around four supernova remnants (SNRs) located near molecular clouds of gas and dust. These SNRs are known to produce shocks -- radio observations have found them emitting very bright radiation from the OH molecule, a sign of powerful shocks. The astronomers wondered whether these strong supernova shocks could also trigger the production of gamma rays by the acceleration of particles, and they selected these four sources for observation.

Writing in this month's Astrophysical Journal, the astronomers report finding gamma ray emission from each of the four SNRs. The next issue was to identify the mechanism. The scientists first considered the possibility that the emission was produced by a pulsar - the spinning, super-dense stellar ash often left behind after a supernova explosion. None of the four SNRs have pulsars, however. The astronomers therefore argue in their paper that the most probable explanation is fast shocks that accelerated particles to speeds close to that of light, leading to the particle decay and the emission of gamma rays. The new results help our understanding of how supernovae affect their environments, as well clarify the details of the mechanisms by which one class of gamma ray is produced.