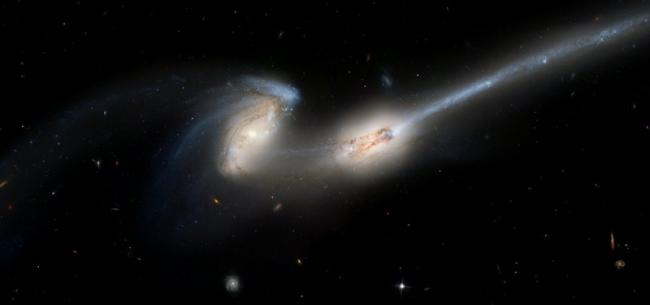

An optical image of NGC 4676 - "The Mice" interacting galaxies. New research at the CfA finds that our Milky Way galaxy will collide with the Andromeda galaxy in another few billion years.

Galaxies frequently collide with one another, leaving evidence for their stupendous interactions nearly everywhere in the sky. Our own Milky Way galaxy, for example, is heading towards its nearest giant neighbor, the Andromeda galaxy, at a rate of about 120 kilometers per second, and predictions claim the two will merge together in another four billion years or so. But it is not only the future of our home galaxy that interests scientists -- these powerful collisions are thought to help produce massive stars that in turn enrich galaxies with chemical elements.

Although astronomers have known for over fifty years that the Milky Way and Andromeda were on a collision course, the details of their dramatic future encounter were poorly understood. Two CfA astronomers, T.J. Cox and Avi Loeb, have now remedied that situation. The Milky Way and Andromeda are the two major (that is, most massive) galaxies in what is called "The Local Group" that includes about forty other, much smaller galaxies all bound together gravitationally. The two astronomers applied their latest computer simulations of interacting galaxies to the Local Group. They included, for the first time in such a detailed simulation, the effects of the dark matter, and since there is nearly five times as much dark matter as normal matter in the Local Group, it plays a pivotal role. They also address one key unknown. Contrary to what one might expect, the transverse motion of Andromeda across the sky is virtually unmeasurable, whereas its motion directly towards us in the Milky Way is easily determined from the wavelength shift of its light via the Doppler effect. That transverse motion nonetheless will affect the future collision, and so the scientists ran their calculations with a range of different possible transverse motions for Andromeda.

The simulations all gave about the same statistical outcome. It is most likely that the Milky Way and Andromeda will collide in only a few billion years to form a new, elliptical-type galaxy that the two astronomers dub "Milkomeda." This timescale is considerably faster than had been expected -- and in fact is well within the lifetime of our sun, which will burn its hydrogen fuel happily (although not without some adjustments) for another seven billion years or so. The simulations also predict that the solar system, because it currently resides about two-thirds of the way from the center to the outer part of our galaxy, stands a very good chance of being ejected into a long tidal tail in the coming collision. In fact, at one point we may even end up being transferred to Andromeda altogether.

The scientists include some speculative thoughts about life on earth during all this, should humanity figure out ways to cope with the more conventional interim developments. They note that the sky might be filled with more comet showers as perturbing stars disrupt the solar system's outer reservoir of material. And, not least, they add that since the accelerating universe will eventually disperse all other galaxies in the cosmos beyond our horizon, in another 100 billion years or so our view of the entire cosmos will consist solely of the residue of this cataclysm:

Milkomeda and its Local Group.