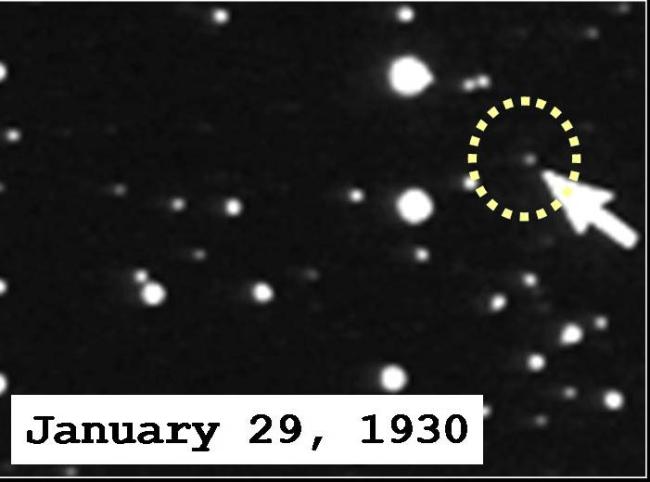

The discovery photograph of Pluto found by Clyde W. Tombaugh of Lowell Observatory in 1930. Astronomers today suspect that there might be a previously unknown Planet 9 in the distant solar system, but a new search at millimeter wavelengths has failed to find any convincing candidate.

The Solar System has eight planets. In 2006, astronomers reclassified Pluto as a dwarf planet, the same class as contains Eris, Sedna, Quaoar, Ceres and perhaps many more solar system small bodies. These are defined approximately as bodies that orbit the Sun but that are not massive enough (unlike regular planets) to gravitationally dominate their environments by clearing away material. Astronomers wonder, though, whether there might not really be a ninth planet previously undiscovered but lurking in the outer reaches of the solar system, perhaps in the giant Oort cloud of objects that begins hundreds of astronomical units (au) from the Sun and extends outward.

The notion that there may be a ninth massive planet in the outer solar system has taken on new appeal with recent data that show that the orbital parameters of some small bodies beyond Neptune (their inclinations, perihelions, and retrograde motions) seem to behave as though they had been influenced by the gravity of a massive object in the outer solar system. Although these data suffer from observational biases and statistical uncertainties, they have triggered renewed interest in the idea of the presence of another planet. This speculative "Planet 9," according to estimates, would be about 5-10 Earth-masses in size and orbit about 400-800 au from the Sun. A planet at this distance would be extremely difficult to spot in normal optical sky searches because of its faintness, even to telescopes like PanSTARRS and LSST. Most solar system objects were discovered at optical wavelengths via their reflected sunlight, but the sunlight they receive drops as one-over-their-distance-from-the-Sun squared; moreover, the reflected portion then travels back to telescopes on Earth and so declines again by a similar factor. In the outer reaches of the solar system these objects, although cold, might emit more infrared radiation than the optical light they reflect, and astronomers in the past have used infrared surveys like the Wide-field Infrared Explorer (WISE) to search, but without success.

The study has been advanced by a team of researchers led by Sigurd Naess of the Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics at the University of Oslo, as a part of the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) collaboration led by Principal Investigator, Professor Suzanne Staggs of Princeton University. CfA astrophysicist Benjamin Schmitt was a member of the team to lead the design, integration, and field operation of ACT's millimeter-wavelength, polarization-sensitive camera - called ACTPol - which took the data central to the Planet 9 study, working with Professor Mark Devlin at the University of Pennsylvania. Although ACT was designed to study the cosmic microwave background radiation, its relatively high angular resolution and sensitivity makes it suitable for this type of search. The astronomers scanned about 87% of the sky accessible from the southern hemisphere over a six year period, and then processed the millimeter images with a variety of techniques including binning and stacking methods that might uncover faint sources but at the expense of losing positional information. Their search found many tentative candidate sources (about 3500 of them) but none could be confirmed, and there were no statistically significant detections. The scientists, however, were able to exclude with 95% confidence a Planet 9 with the above-estimated properties within the surveyed area, results that are generally consistent with other null searches for Planet 9. The results cover only about 10-20% of the possibilities, but other sensitive millimeter facilities are coming online and should be able to complete this search for Planet 9 as hypothesized.

Reference: "The Atacama Cosmology Telescope: A Search for Planet 9," Sigurd Naess et al. The Astrophysical Journal 923, 224, 2021.