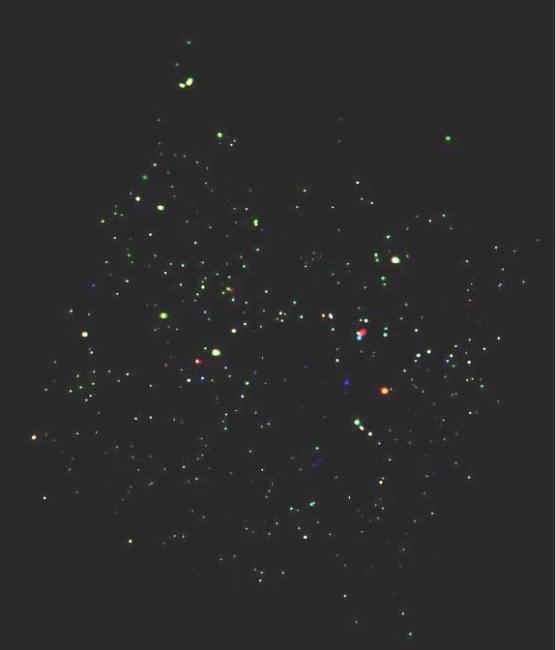

This is a false-color X-ray image of a field of galaxies as seen in a survey done by the Chandra X-ray Observatory. The image covers a region of the sky about equal to the size of two full-moons. Red corresponds to low-energy X-ray emitting galaxies, green to intermediate energy X-ray galaxies, and blue to objects emitting high energy X-rays - about ten times more energetic than those seen in red. One result apparent in this image, apart from the fact that so many galaxies emit X-rays, is the wide range of galaxy types.

Astronomers have only modest laboratories to probe the mysteries of the cosmos. Mostly they have to rely on meticulous and clever observations of remote phenomena. Identifying the most interesting objects for scrutiny has, therefore, always been an important astronomical task. Systematic surveys of regions of the sky at specific wavelengths, for example, turn up lists of expected and unexpected objects for subsequent study. The SWIRE survey (the Spitzer Wide-area Infra-Red Extragalactic survey) scanned a region of the sky as large as 200 full moons in each of the seven infrared cameras on the Spitzer Space Telescope. The prime goal of SWIRE is the study of the structure, evolution, and environments of galaxies out to distances so far that the light has traveled from them to us for ten billion years, about 70% of the age of the universe.

CfA astronomers Belinda Wilkes and Dong-Woo Kim, along with ten colleagues, used the Chandra X-ray Observatory to observe the best 2% of the large SWIRE region (where "best" is defined here by this region's having no known bright sources and being comparatively free of contaminating emission from our Milky Way). Some galaxies are extremely luminous because they have supermassive black holes at their centers. X-rays are a key diagnostic of these active galactic nuclei (AGN) because the X-rays measure material accreting onto the vicinity of the black hole. X-rays can in this way discriminate AGN from galaxies that are bright for other reasons, for example, because of bursts of star formation.

The astronomers found that nearly every one of the 775 galaxies they found with Chandra were also detected in the SWIRE survey. However, they note significantly that there is no apparent relationship in general between the observed brightnesses at infrared and X-ray wavelengths. This result implies that the galaxies have a wide range of internal properties still to be deciphered. On the other hand, the team does find, contrary to conventional methodology, that mid-infrared brightness flux is a much better detector of powerful galactic jet activity than is optical emission. The new results are just the start of a series of more detailed analyses, but already confirm the importance of sensitive, unbiased studies of large regions of the sky at many wavelengths.