Uhuru

The Uhuru X-ray Explorer Satellite was the first spacecraft dedicated to X-ray astronomy. During its mission in the early 1970s, Uhuru mapped the X-ray sky. It provided the first observational evidence for black holes, revealed that galaxy clusters contain hot X-ray-emitting gas, and charted the behavior of neutron stars in binary systems. The observatory was named Uhuru, the Swahili word meaning “freedom”, in honor of Kenyan independence and because the rocket carrying the spacecraft was launched into orbit from a site off the coast of Kenya near Mombasa. The success of the Uhuru satellite led the way for all subsequent space telescopes, from the Einstein Observatory to NASA’s flagship Chandra X-ray Observatory.

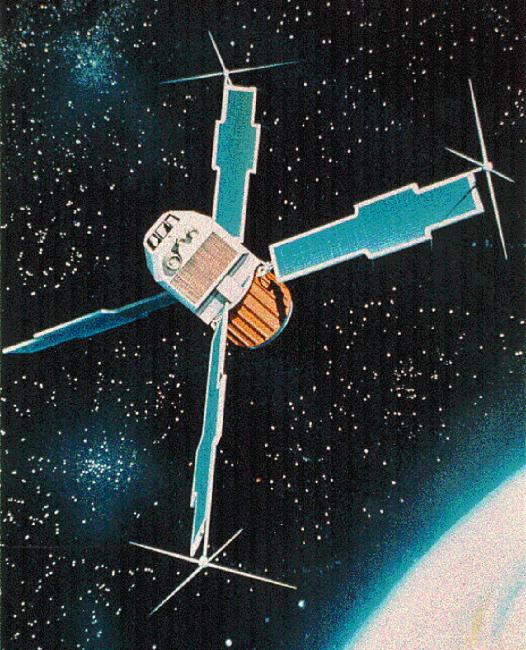

An artistic depiction of Uhuru, the first satellite observatory devoted to X-ray astronomy. Uhuru operated from 1970 to 1973, providing some of the first observations of black holes, galaxy clusters, and other cosmic X-ray sources.

The Spacecraft and the Science

Almost all cosmic X-rays are blocked by Earth’s atmosphere, which requires astronomers to put X-ray telescopes as high up as possible. The earliest X-ray missions were detectors on rockets launched into the upper atmosphere, which limited their size and abilities. Uhuru, also designated Explorer 42 or Small Astronomical Satellite 1, was the first spacecraft designed for X-ray astronomy. It was launched into orbit on December 12, 1970, the seventh anniversary of Kenyan independence.

Because the scientific instrument was small — only 65 kilograms (143 pounds) in mass — and X-ray focusing technology was still being developed, Uhuru wasn’t a telescope in the usual sense. Instead, Uhuru used “proportional counters”, which were a set of sensitive gas-filled detectors which generated electrical signals with a strength proportional to the energy of the X-ray photons striking them. These were placed behind a collimator array, which looked much like a box of straws.

Uhuru’s orbit and rotation allowed it to survey roughly 95 percent of the sky, locating 339 X-ray sources during its lifetime. Those included X-ray binaries: a neutron star or black hole which pulls matter off a star orbiting it, creating a hot X-ray-emitting disk of gas. One of those binaries, named Cygnus X-1, was the first black hole ever discovered. Uhuru also demonstrated that galaxy clusters contain hot plasma, making them powerful X-ray sources.

The Uhuru mission lasted a little over two years, ending in March 1973, while the satellite itself reentered Earth’s atmosphere in 1979. As the first orbiting X-ray observatory, Uhuru was the direct ancestor of all modern advanced X-ray telescopes, including NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the next-generation Lynx Observatory.

- Supernovas & Remnants

- Quasars & Other Active Black Holes

- Black Holes

- Neutron Stars and White Dwarfs

- Jets, Outflows and Shocks