Jets, Outflows and Shocks

Matter under extremes of temperature, magnetic field, and density can behave in surprising ways. The environments around stars, black holes, and other astronomical objects regularly produce violent behaviors, including jets of fast-moving matter, powerful outflows of particles, and shock waves. Extreme phenomena of this sort are responsible for everything from auroras on Earth to the formation of new stars in the wake of a supernova explosion. Outflows, shocks, and jets occur in a wide variety of astronomical systems, but many of the rules governing them are the same.

Our Work

Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian scientists study the extreme phenomena of shocks, jets, and outflows in many ways:

-

Observing black holes to see how jets form in the first place. While astronomers understand the big picture of how infalling matter drives jets shooting outward, jets form very close to the object that makes them — which is a small region of space, nearly impossible to observe even with the most powerful telescopes. Using the Smithsonian’s Submillimeter Array (SMA) observatory and other telescopes, researchers are able to parse some details of these hard-to-see systems.

Extreme Jets -

Studying gamma rays emitted by jets emitted by the supermassive black holes called “blazars”. These objects produce some of the most powerful jets in the cosmos, and their apparent brightness is enhanced by the fact that the jets are aimed toward Earth. Using the Very Energetic Radiation Imaging Telescope Array System (VERITAS), astronomers can measure the gamma rays emitted by these extreme jets.

VERITAS Observes Distant Blazar -

Observing the shock waves produced by colliding galaxy clusters. Clusters contain huge amounts of hot plasma, and collisions result in the plasma smashing together. Astronomers use NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and other telescopes to observe these shock fronts, which help us understand how galaxy clusters form and evolve.

Colliding Galaxy Clusters -

Using the Chandra X-ray Observatory to understand the extreme environment around newborn stars. Star-forming regions are messy places, with lots of detritus to block our view. In a few cases, however, astronomers can peer into the region close to the star and witness the way infalling matter produces shock fronts.

X-Ray Emission from Young Stars -

Maintaining a database of shock waves observed by various spacecraft within the Solar System. Magnetic fields from Earth and Jupiter generate shock waves from particles streaming from the Sun. Tracking these shocks helps researchers monitor solar “weather” and reveals how Earth’s magnetic field protects us.

-

Measuring the shock waves produced by supernovas and their remnants. Supernova explosions send a huge amount of matter outward, producing shocks in the surrounding gas. However, that material can also send shock waves back in toward the original explosion. Light from these “reverse shocks” illuminate the supernova remnant, providing us with details about these complex systems.

Mach 1000 Shock Wave Lights Supernova Remnant -

Studying how black holes jets pump energy into their surroundings, in a process known as “feedback”. The feedback process can throttle the formation of new stars inside the black hole’s host galaxy, in a complex interaction between the black hole and its surroundings.

Chandra Finds Evidence for Serial Black Hole Eruptions

The Magnetic and Gravitational Dance of Particles

High temperatures tend to strip electrons from their atoms, turning gas into plasma: a fluid of electrically-charged particles. These particles swirl around in magnetic fields, which can accelerate them to very high energies. Charged particles also generate magnetic fields, which means extreme astronomical environments are a complicated tangle of magnetism, gravity, and plasmas. The study of these systems is called “magnetohydrodynamics”.

Dramatic magnetic environments are produced in many astronomical systems, from newborn stars to the supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies. As wildly different as these systems are on the surface, they all involve plasmas being driven by magnetic fields. For that reason, they produce many similar effects:

-

Gravity and rotation act together to shape the motion of particles into a disk near a black hole, neutron star, newborn star, or other compact object. The tangled magnetic fields produced in these systems funnel particles into narrow jets that shoot away from the central object. Particles in these jets can move close to the speed of light, emitting light at radio, X-ray, and gamma-ray wavelengths. Jets from supermassive black holes can dwarf their host galaxies, and are sometimes bright enough to be seen from billions of light-years away.

-

When fast-moving particles run into something else — a cloud of gas or the magnetic field of another object — that collision abruptly decreases their speed, producing a “shock wave”. These shocks heat and compress the gas. Relatively slow shocks emit infrared light, while faster shocks produce UV and X-rays, along with the energetic particles known as cosmic rays. Jets produce shock waves when they strike interstellar gas, and shocks also happen when particles blasted out by a supernova hit surrounding gas. Closer to home, charged particles in the solar wind strike Earth’s magnetic field, producing a “bow shock”, named for its resemblance to the ripples made by the bow of a moving ship.

-

Jets made by newborn stars crash into the nebula that gave birth to the stars. The result is a narrow chain of shocks and an “outflow”, which looks like an expanding cone of flowing matter surrounding the original jet. Outflows also occur in dying stars, giving some of the clouds known as planetary nebulas their distinctive shape.

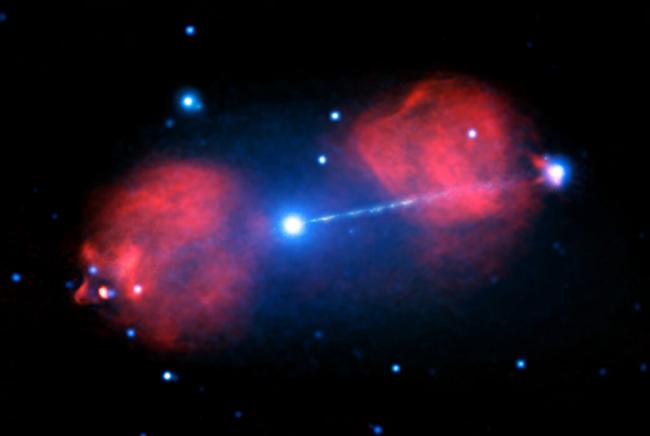

The supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy Pictor A sends huge jets of matter into intergalactic space at near light-speed. This image shows the jets in X-ray (blue color) and radio (red) light.

Shocking Behavior

Shock waves form when particles are moving faster than the speed of sound in that environment, thanks to something driving them at supersonic speeds. Bow shocks and other shock fronts happen where those supersonic particles are suddenly forced to slow down.

Though they’re definitely extreme phenomena, shocks are also very common. In addition to bow shocks produced by planets like Earth and Jupiter, astronomers have observed shocks from fast-moving stars plowing through interstellar gas, and shock waves from colliding galaxy clusters. On a smaller scale, shock waves driven by solar storms can endanger satellites and astronauts.

When shocks compress interstellar gas, they can spur the birth of new stars. That means the death of massive stars in supernovas can lead to the creation of the next generation. Since star formation itself produces outflows and shocks, in some instances star birth is a feedback process. This is one reason why many stars form in clusters at the same time. Astronomers study many different ways shocks can give rise to star formation, which include jets from supermassive black holes.

- Solar & Heliospheric Physics

- Theoretical Astrophysics

- Stellar Astronomy

- The Milky Way Galaxy

- Computational Astrophysics

Related News

CfA Celebrates 25 Years with the Chandra X-ray Observatory

Astronomers Unveil Strong Magnetic Fields Spiraling at the Edge of Milky Way’s Central Black Hole

Black Hole Fashions Stellar Beads on a String

Christine Jones Forman Elected to National Academy of Sciences

Brightest Gamma-Ray Burst Ever Observed Reveals New Mysteries of Cosmic Explosions

Hydrogen Masers Reveal New Secrets of a Massive Star

‘We’ve Never Seen Anything Like This Before:’ Black Hole Spews Out Material Years After Shredding Star

New Study Sheds Light on Why Stellar Populations Are So Similar in Milky Way

A Galaxy Cluster with Two Pairs of X-Ray Cavities

Did a Black Hole Eating a Star Generate a Neutrino? Unlikely, New Study Shows

Telescopes and Instruments

Chandra

Visit the Chandra Website

Hinode

Visit the Hinode/XRT Website

SOFIA (Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy)

Visit the SOFIA Website

The Submillimeter Array - Maunakea, HI

Visit the Submillimeter Array Website