Through an internship and now as a research collaborator with the Center for Astrophysics, Rachel Nere is fulfilling her dream.

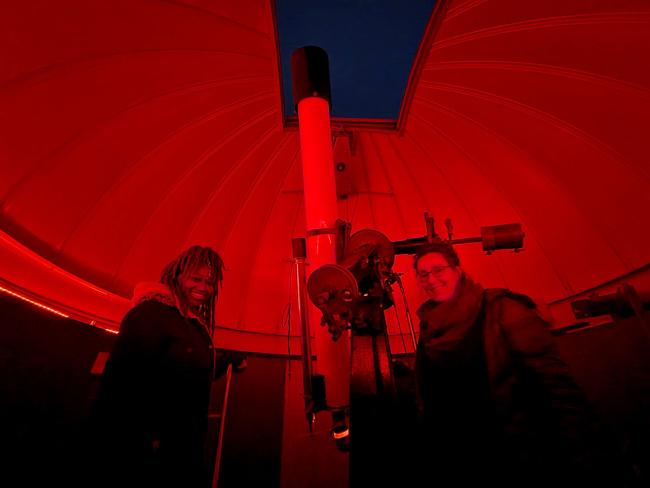

Rachel Nere and Regina Jorgenson, Director of Astronomy at the Nantucket Maria Mitchell Association, at the Maria Mitchel Observatory.

The answers that little kids give to the question "What do you want to be when you grow up?" often change from week to week. Not so for Rachel Nere.

She recalls one summer night when she was six years old, running around with her father and siblings in a Boston-area backyard. "One moment I was playing and having fun, and the next I was just looking up wondering what made the universe tick," Nere says. "That sealed it for me. Since then, I've been very adamant about being a scientist."

A senior physics major at the University of Massachusetts Boston, Nere interned at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian in summer 2021 and has continued to conduct research for the institution. She started working with the Center for Astrophysics through the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) Latino Initiative Program. Launched in 2015 by Christine Crowley, the CfA's fellowship program director, the program encourages undergraduates from underrepresented backgrounds to pursue careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

The Latino Initiative Program, or LIP, is deeply meaningful to Rodolfo "Rudy" Montez Jr., an astrophysicist and the program's former co-director. As Montez Jr. started attending national astronomy conferences in the early 2000s, he realized how few Latinos and other people of color were represented in the field of astronomy — a persistent issue in many STEM disciplines.

"With the Latino Initiative Program and many other programs that now exist like it," Montez Jr. says, "we're trying to help people realize their full potential."

Undergraduate students accepted to LIP pair up with mentors to work on summerlong research projects. Montez Jr. chose Nere as his mentee on a project dedicated to identifying and better understanding a rare kind of star called an RV Tauri variable (named after the first such star of its kind, identified back in the early 1900s).

Called RV Taus for short, these stars are older versions of Sunlike stars that have run out of hydrogen fuel in their core. The core compresses and draws in outer layers of hydrogen, which resumes fusing in a shell around the core. The resulting energy release causes the over-the-hill star to balloon in size and transform into a so-called red giant.

As some red giant stars evolve further, they enter the RV Tau phase. The phase is marked by distinct fluctuations in brightness when the star's light output alternates between shallow and deep minima: from fully bright to less bright, then back to fully bright, then down to least bright, and back again to fully bright, and so on. Stars only remain in this variable stage, however, for approximately 300,000 years — a mere cosmic eyeblink, considering most stars' lifetimes stretch across billions of years — making these stellar specimens a rare breed.

"It's harder to find these RV Tau stars, so it's harder to study them," says Nere.

Other kinds of variable stars can mimic the appearance of RV Taus, complicating matters, especially when recorded observations of a given star are cursory and incomplete, as is often the case. Accordingly, numerous RV Tau stars have been historically misclassified.

"There are a lot of stars in catalogs that astronomers have been calling RV Taus but really aren't," says Montez Jr. "That has muddled our understanding of this phase of stellar evolution."

The first step of the summer project involved reviewing a recently compiled observational database of stars that contained scores of stars historically classified as RV Taus. The researchers then inspected the stellar data in detail, successfully weeding out a bunch of clearly mislabeled RV Taus.

"We're revealing the 'imposter' RV Taus," Nere quips.

To address a handful of stars for which there is not enough observational evidence to rule them in or out as RV Taus, the researchers booked time at an observatory to gather more data. Montez Jr. has a working relationship with the Maria Mitchell Observatory — named after the first American woman astronomer — out on Nantucket Island, and the original plan called for an observing run in August 2021. The expedition was canceled, however, due to COVID-19 concerns.

Nere, thankfully, had a backup plan in place. Shortly after she started her internship at the Center for Astrophysics, she won a VanguardSTEM Hot Science Summer award, presented by The SeRCH Foundation, Inc, a not-for-profit education organization. Part crowdfunding and part grant, the award provides financial backing for research projects launched by Black, Indigenous, women of color, non-binary people of color and marginalized communities of all gender identities.

This additional funding allowed Nere to stay on at the Center for Astrophysics as a collaborator through 2022. Importantly for the project, and poignantly for Nere, scheduling and pandemic constraints have eased to allow her to journey, at last, to the Maria Mitchel Observatory in March 2022 — her first time ever working in a professional astronomical observatory.

Alas, sky conditions did not cooperate, and "we got 'clouded out'," says Nere, who is already adept at deploying astronomer lingo.

But she did get to practice operating the observatory's 24-inch reflecting telescope, a golf cart-sized machine controlled by a computer terminal, as well as a smaller refracting telescope that Nere looked through the eyepiece of and manipulated by hand.

"I don't want to use this word as a scientist, but it was a 'magical' experience," Nere says. "Just looking at the telescopes and seeing how they worked, I was in awe of it all. It was my six-year-old dream coming true."

Future trips to Nantucket are slated for late summer and early fall 2022. Spacing out the observations in this way is necessary for verifying RV Taus; the stars undergo their telltale brightness changes every 30 to 60 days or so.

Montez Jr. expects that cleaning up stellar catalogs and proffering a sizable RV Tau population for thorough study will enable astronomers to ultimately nail down the mechanisms behind the enigmatic stars' fickle luminosity.

Nere, meantime, plans to graduate in December 2022 and is looking ahead to pursuing a PhD in physics and astronomy. She credits Montez Jr. for helping her grow as a young scientist.

"Working with Rudy has been amazing and he is a very supportive, patient, and understanding advisor," says Nere. "His love for astronomy makes me enjoy the work that much more."