CfA astronomers have found strong evidence for a supermassive black hole in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy to the Milky Way

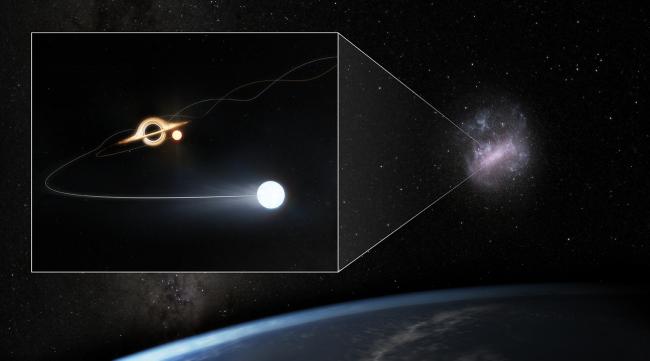

Artist’s impression of a hypervelocity star ejected from the Large Magellanic Cloud (shown on right). When a binary star system ventures too close to a supermassive black hole, the intense gravitational forces tear the pair apart. One star is captured into a tight orbit around the black hole, while the other is flung outward at extreme velocities—often exceeding millions of miles per hour—becoming a hypervelocity star. The inset illustration depicts this process: the original binary’s orbital path is shown as interwoven lines, with one star being captured by the black hole (near center of inset) while the other is ejected into space (lower right).

Credit: CfA/Melissa Weiss

Cambridge, MA - Astronomers have discovered strong evidence for the closest supermassive black hole outside of the Milky Way galaxy. This giant black hole is located in the Large Magellanic Cloud, one of the nearest galactic neighbors to our own.

To make this discovery, researchers traced the paths with ultra-fine precision of 21 stars on the outskirts of the Milky Way. These stars are traveling so fast that they will escape the gravitational clutches of the Milky Way or any nearby galaxy. Astronomers refer to these as "hypervelocity" stars.

Similar to how forensic experts recreate the origin of a bullet based on its trajectory, researchers determined where these hypervelocity stars come from. They found that about half are linked to the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. However, the other half originated from somewhere else: a previously-unknown giant black hole in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC).

"It is astounding to realize that we have another supermassive black hole just down the block, cosmically speaking," said Jesse Han of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian (CfA), who led the new study. "Black holes are so stealthy that this one has been practically under our noses this whole time."

The researchers found this secretive black hole by using data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission, a satellite that has tracked more than a billion stars throughout the Milky Way with unprecedented accuracy. They also used an improved understanding of the LMC’s orbit around the Milky Way recently obtained by other researchers.

"We knew that these hypervelocity stars had existed for a while, but Gaia has given us the data we need to figure out where they actually come from," said co-author Kareem El-Badry of Caltech in Pasadena, California. "By combining these data with our new theoretical models for how these stars travel, we made this remarkable discovery."

Hypervelocity stars are created when a double-star system ventures too close to a supermassive black hole. The intense gravitational pull from the black hole rips the two stars apart, capturing one star into a close orbit around it. Meanwhile, the other orphaned star is jettisoned away at speeds exceeding several million miles per hour -- and a hypervelocity star is born.

A significant piece of the team’s research was a prediction by their theoretical model that a supermassive black hole in the LMC would create a cluster of hypervelocity stars in one corner of the Milky Way because of how the LMC moves around the Milky Way. The stars ejected along the direction of the LMC’s motion should receive an extra boost in speed. Indeed, their data revealed the existence of such a cluster.

The team found that the properties of the hypervelocity stars cannot be explained by other mechanisms, such as stars being ejected when their companions undergo a supernova explosion, or stars being ejected by a mechanism like that described above for a double star system, but without a supermassive black hole being involved.

"The only explanation we can come up with for this data is the existence of a monster black hole in our galaxy next door," said co-author Scott Lucchini, also of CfA. "So in our cosmic neighborhood it’s not just the Milky Way’s supermassive black hole evicting stars from its galaxy."

Using the speeds of the stars and the relative number of ones ejected by the LMC and Milky Way supermassive black holes, the team determined that the mass of the LMC black hole is about 600,000 times the mass of the Sun. For comparison, the supermassive black hole in the Milky Way has about 4 million solar masses. Elsewhere in the Universe, there are supermassive black holes with billions of times more mass than the Sun.

A paper describing these results has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal and is available here.

About the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian

The Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian is a collaboration between Harvard and the Smithsonian designed to ask—and ultimately answer—humanity's greatest unresolved questions about the nature of the universe. The Center for Astrophysics is headquartered in Cambridge, MA, with research facilities across the U.S. and around the world.

Media Contact

Peter Edmonds

Interim CfA Public Affairs Officer

Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian

617-571-7279

pedmonds@cfa.harvard.edu

Related News

NASA's Hubble, Chandra Find Supermassive Black Hole Duo

Event Horizon Telescope Makes Highest-Resolution Black Hole Detections from Earth

CfA Celebrates 25 Years with the Chandra X-ray Observatory

CfA Astronomers Help Find Most Distant Galaxy Using James Webb Space Telescope

Astronomers Unveil Strong Magnetic Fields Spiraling at the Edge of Milky Way’s Central Black Hole

Black Hole Fashions Stellar Beads on a String

M87* One Year Later: Proof of a Persistent Black Hole Shadow

Unexpectedly Massive Black Holes Dominate Small Galaxies in the Distant Universe

Unveiling Black Hole Spins Using Polarized Radio Glasses

A Supermassive Black Hole’s Strong Magnetic Fields Are Revealed in a New Light

Projects

AstroAI

DASCH (Digital Access to a Sky Century @ Harvard)

For that reason, the DASCH (Digital Access to a Sky Century @ Harvard) team are working to digitize the plates for digital storage and analysis. The process can also lead to new discoveries in old images, particularly of events that change over time, such as variable stars, novas, or black hole flares.

GMACS

For Scientists

Sensing the Dynamic Universe

SDU Website