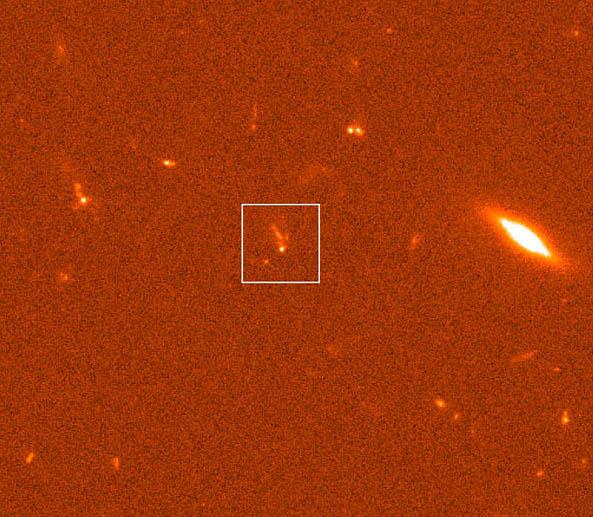

A NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope image of the rapidly fading visible-light fireball from a gamma-ray burst (GRB) in a distant galaxy. A new study used the spectra of 140 GRB afterglows to estimate the amount of ionizing radiation from massive stars that escapes from galaxies to ionize the intergalactic medium, and finds the surprising result that it is very small.

The sparsely distributed hot gas that exists in the space between galaxies, the intergalactic medium, is ionized. The question is, how? Astronomers know that once the early universe expanded and cooled enough, hydrogen (its main constituent) recombined into neutral atoms. Then, once newly formed massive stars began to shine in the so-called “era of reionization,” their extreme ultraviolet radiation presumably ionized the gas in processes that continue today. One of the key steps, however, is not well understood, namely the extent to which the stellar ionizing radiation escapes from the galaxies into the IGM. Only if the fraction escaping was high enough during the era of reionization could starlight have done the job, otherwise some other significant source of ionizing radiation is required. That might imply the existence of an important population of more exotic objects like faint quasars, X-ray binary stars, or perhaps even decaying/annihilating particles.

Direct studies of extreme ultraviolet light are difficult because the neutral gas absorbs it very strongly. Because the universe is expanding, the spectrum absorbed covers more and more of the optical range with distance until optical observations of cosmologically remote galaxies are essentially impossible. CfA astronomer Edo Berger joined a large team of colleagues to estimate the amount of absorbing gas by looking at the spectra of gamma-ray burst (GRB) afterglows. GRBs are very bright bursts of radiation produced when the core of a massive star collapses. They are bright enough that when their radiation is absorbed in narrow spectral features by gas along the line-of sight, those features can be measured and used to calculate the amount of absorbing atomic hydrogen. That number can then be directly converted into an escape fraction for the ultraviolet light of the associated galaxy. Although a single observation of a GRB in one galaxy does not provide a robust measure, a sample of GRBs is thought to be able to provide a representative measure across all sightlines to massive stars.

The astronomers carefully measured the spectra of 140 GRB afterglows in galaxies ranging as far away as epochs slightly less than one billion years after the big bang. They find a remarkably small escape fraction – less than about 1% of the ionizing photons make it out into the intergalactic medium. The dramatic result finds that stars provide only a small contribution to the ionizing radiation budget in the universe from that early period until today, not even in galaxies actively making new stars. The authors discuss possible reasons why GRBs might not provide an accurate measure of the absorption, although none is particularly convincing. The result needs confirmation and additional measurements, but suggests that a serious reconsideration of the ionizing budget of the intergalactic medium of the universe is needed.

"The Fraction of Ionizing Radiation from Massive Stars That Escapes to the Intergalactic Medium," N. R. Tanvir et al. MNRAS 483, 5380, 2019