Young Sun-like Star Shows a Magnetic Field Was Critical for Life on the Early Earth

Cambridge, MA -

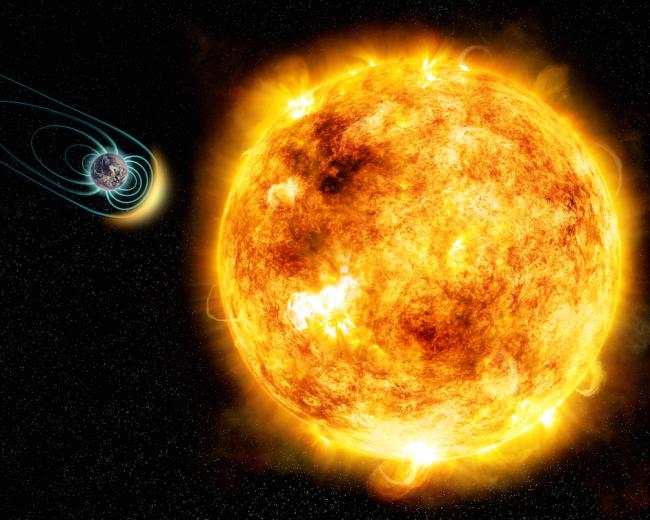

Nearly four billion years ago, life arose on Earth. Life appeared because our planet had a rocky surface, liquid water, and a blanketing atmosphere. But life thrived thanks to another necessary ingredient: the presence of a protective magnetic field. A new study of the young, Sun-like star Kappa Ceti shows that a magnetic field plays a key role in making a planet conducive to life.

"To be habitable, a planet needs warmth, water, and it needs to be sheltered from a young, violent Sun," says lead author Jose-Dias Do Nascimento of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) and University of Rio G. do Norte (UFRN), Brazil.

Kappa Ceti, located 30 light-years away in the constellation Cetus, the Whale, is remarkably similar to our Sun but younger. The team calculates an age of only 400-600 million years old, which agrees with the age estimated from its rotation period (a technique pioneered by CfA astronomer Soren Meibom). This age roughly corresponds to the time when life first appeared on Earth. As a result, studying Kappa Ceti can give us insights into the early history of our solar system.

Like other stars its age, Kappa Ceti is very magnetically active. Its surface is blotched with many giant starspots, like sunspots but larger and more numerous. It also propels a steady stream of plasma, or ionized gases, out into space. The research team found that this stellar wind is 50 times stronger than our Sun's solar wind.

Such a fierce stellar wind would batter the atmosphere of any planet in the habitable zone, unless that planet was shielded by a magnetic field. At the extreme, a planet without a magnetic field could lose most of its atmosphere. In our solar system, the planet Mars suffered this fate and turned from a world warm enough for briny oceans to a cold, dry desert.

The team modeled the strong stellar wind of Kappa Ceti and its effect on a young Earth. The early Earth's magnetic field is expected to have been about as strong as it is today, or slightly weaker. Depending on the assumed strength, the researchers found that the resulting protected region, or magnetosphere, of Earth would be about one-third to one-half as large as it is today.

"The early Earth didn't have as much protection as it does now, but it had enough," says Do Nascimento.

Kappa Ceti also shows evidence of "superflares" -- enormous eruptions that release 10 to 100 million times more energy than the largest flares ever observed on our Sun. Flares that energetic can strip a planet's atmosphere. By studying Kappa Ceti, researchers hope to learn how frequently it produces superflares, and therefore how often our Sun might have erupted in its youth.

This research has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters and is available online. This set of Kappa Ceti observations were part of the Bernard Lyot Telescope's Bcool Large Program.

Headquartered in Cambridge, Mass., the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) is a joint collaboration between the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory and the Harvard College Observatory. CfA scientists, organized into six research divisions, study the origin, evolution and ultimate fate of the universe.

For more information, contact:

Christine Pulliam

Media Relations Manager

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

617-495-7463

cpulliam@cfa.harvard.edu