Cambridge, MA -

A giant black hole ripped apart a star and then gorged on its remains for about a decade, according to astronomers. This is more than ten times longer than any observed episode of a star's death by black hole.

Researchers made this discovery using data from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and Swift satellite as well as ESA's XMM-Newton.

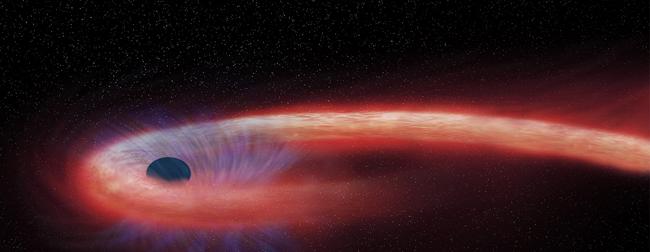

The trio of orbiting X-ray telescopes found evidence for a "tidal disruption event" (TDE), wherein the tidal forces due to the intense gravity from a black hole can destroy an object — such as a star — that wanders too close. During a TDE, some of the stellar debris is flung outward at high speeds, while the rest falls toward the black hole. As it travels inwards to be ingested by the black hole, the material heats up to millions of degrees and generates a distinct X-ray flare.

"We have witnessed a star's spectacular and prolonged demise," said Dacheng Lin from the University of New Hampshire in Durham, New Hampshire, who led the study. "Dozens of tidal disruption events have been detected since the 1990s, but none that remained bright for nearly as long as this one."

The extraordinary long bright phase of this event spanning over ten years means that among observed TDEs this was either the most massive star ever to be completely torn apart during one of these events, or the first where a smaller star was completely torn apart.

The X-ray source containing this force-fed black hole, known by its abbreviated name of XJ1500+0154, is located in a small galaxy about 1.8 billion light years from Earth.

The source was not detected in a Chandra observation on April 2nd, 2005, but was detected in an XMM-Newton observation on July 23rd, 2005, and reached peak brightness in a Chandra observation on June 5, 2008. These observations show that the source became at least 100 times brighter in X-rays. Since then, Chandra, Swift, and XMM-Newton have observed it multiple times.

The sharp X-ray vision of Chandra data shows that XJ1500+0154 is located at the center of its host galaxy, the expected location for a supermassive black hole.

The X-ray data also indicate that radiation from material surrounding this black hole has consistently surpassed the so-called Eddington limit, defined by a balance between the outward pressure of radiation from the hot gas and the inward pull of the gravity of the black hole.

"For most of the time we've been looking at this object, it has been growing rapidly," said co-author James Guillochon of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass. "This tells us something unusual — like a star twice as heavy as our Sun — is being fed into the black hole."

The conclusion that supermassive black holes can grow, from TDEs and perhaps other means, at rates above those corresponding to the Eddington limit has important implications. Such rapid growth may help explain how supermassive black holes were able to reach masses about a billion times higher than the sun when the universe was only about a billion years old.

"This event shows that black holes really can grow at extraordinarily high rates," said co-author Stefanie Komossa of QianNan Normal University for Nationalities in Duyun City, China. "This may help understand how precocious black holes came to be."

Based on the modeling by the researchers the black hole's feeding supply should be significantly reduced in the next decade. This would result in XJ1500+0154 fading in X-ray brightness over the next several years.

A paper describing these results appears on February 6th issue in Nature Astronomy and is available online. NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, manages the Chandra program for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, controls Chandra's science and flight operations.

A labeled image, a podcast, and a video about the findings are available at:

For more Chandra images, multimedia and related materials, visit:

Headquartered in Cambridge, Mass., the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) is a joint collaboration between the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory and the Harvard College Observatory. CfA scientists, organized into six research divisions, study the origin, evolution and ultimate fate of the universe.

For more information, contact:

Megan Watzke

Chandra X-ray Center, Cambridge, Mass.

617-496-7998

mwatzke@cfa.harvard.edu

Christine Pulliam

Media Relations Manager

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

617-495-7463

cpulliam@cfa.harvard.edu

Related News

CfA Celebrates 25 Years with the Chandra X-ray Observatory

Unexpectedly Massive Black Holes Dominate Small Galaxies in the Distant Universe

Christine Jones Forman Elected to National Academy of Sciences

Astronomers Reveal First Image of the Black Hole at the Heart of Our Galaxy

Bringing Black Holes to Light

Connecting the Dots: From Black Hole Theory to Actual Images

Belinda Wilkes Named Lifetime AAAS Fellow

Quasars as Cosmic Standard Candles

"X-Ray Magnifying Glass" Enhances View of Distant Black Holes

Wandering Black Holes

Projects

AstroAI

Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI)

GMACS

For Scientists

James Webb Space Telescope Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES)

Sensing the Dynamic Universe

SDU Website